My fortieth year.

Entering middle age I found myself flying across the Atlantic Ocean towards my place of birth. Thousands of feet above the ground en route to Bucharest, Romania, the city where I was born, the city my family came from, the city I haven’t seen in thirty-two years.

I was six years old when my family left, yet memories remain, emotions, a lot of emotions mixed in with my sense of self as an immigrant and in my identity as a Romanian. I was going home, my real home, the land of my ancestors.

Yet, my stomach was in knots, gripped by fear and anxiety. Will I feel at home, will this trip dispel the magical and spiritual memories of my youth? So much of what I remember is tinged in a smoky, golden brown patina, like the inside of a sacred church through the haze of burning incense. My memories are disjointed, out of order, out of narrative. I remember emotions, feelings, and tastes. So much is on the periphery of consciousness, timeless and hard to grasp, like illusions sighted at the corner of my vision.

Time with my maternal Grandfather Dimi and grandmother at the apartment on Brezoianu. Days spent playing in Cismigiu Park. God, I remember such sadness at Dimi's death. I barely remember him but I love him so much. He is just out of grasp, a figure that is an idea, yet still a constant presence in my life. His love of books, his erudition. I’m sad, I haven’t thought about him in years but here I am, eyes filled with tears.

To great relief and joy, I felt at home. Bucharest didn’t seem new and alien, like so many of the cities I’ve visited. No, Bucharest felt familiar, different, changed, yet the same. I was at home in the house my father, himself gone for over twenty years, grew up in, a house that used to belong to his grandfather. I didn’t feel foreign, strange, or out of place.

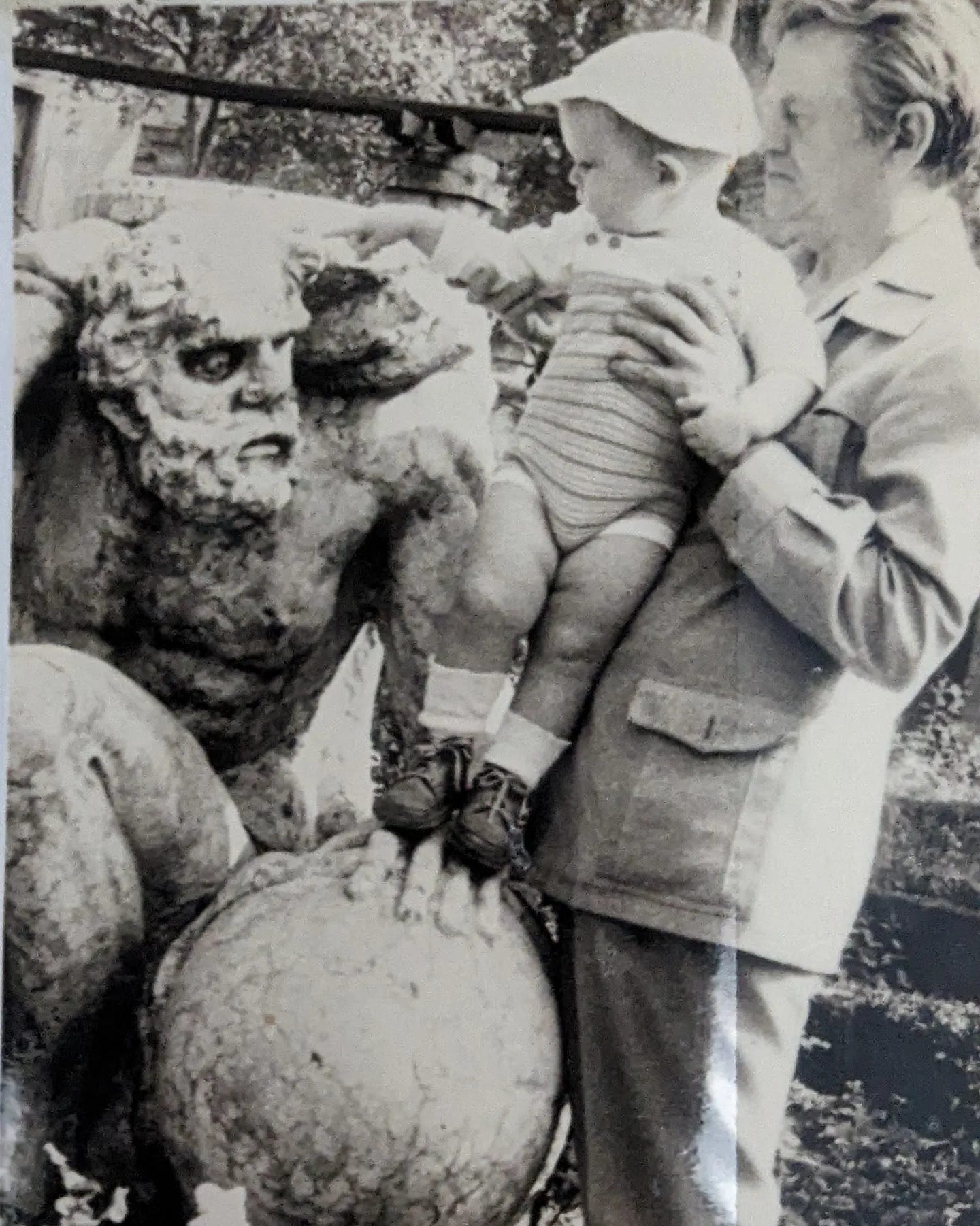

I spent days wandering the streets of central Bucharest, my childhood memories my only map. Somehow I found my way to Cismigiu and thirty-two years later I remembered where the statue of Atlas was, the statue that Dimi placed me on as a child to take one of the only pictures I have of him. I came back a few days later and took a picture with my daughter.

My daughter played in the same park I played in as a child. She spent nights in the same house my father grew up in, and his father and his father’s father made her the 5th generation to walk through the rooms of the now-aging house. We walked the streets of a city, strange yet familiar, a city filled with romantic houses, some restored, some in ruins, next to interwar Art Deco buildings, brutalist communist era bocks, and modern, 21st-century graffiti-covered buildings housing Starbucks and Burger Kings. I visited my father's father grave for the first time. We ate a great dinner at the restaurant where my parents met. I drank coffee beneath the balcony of the apartment where my mother spent her childhood.

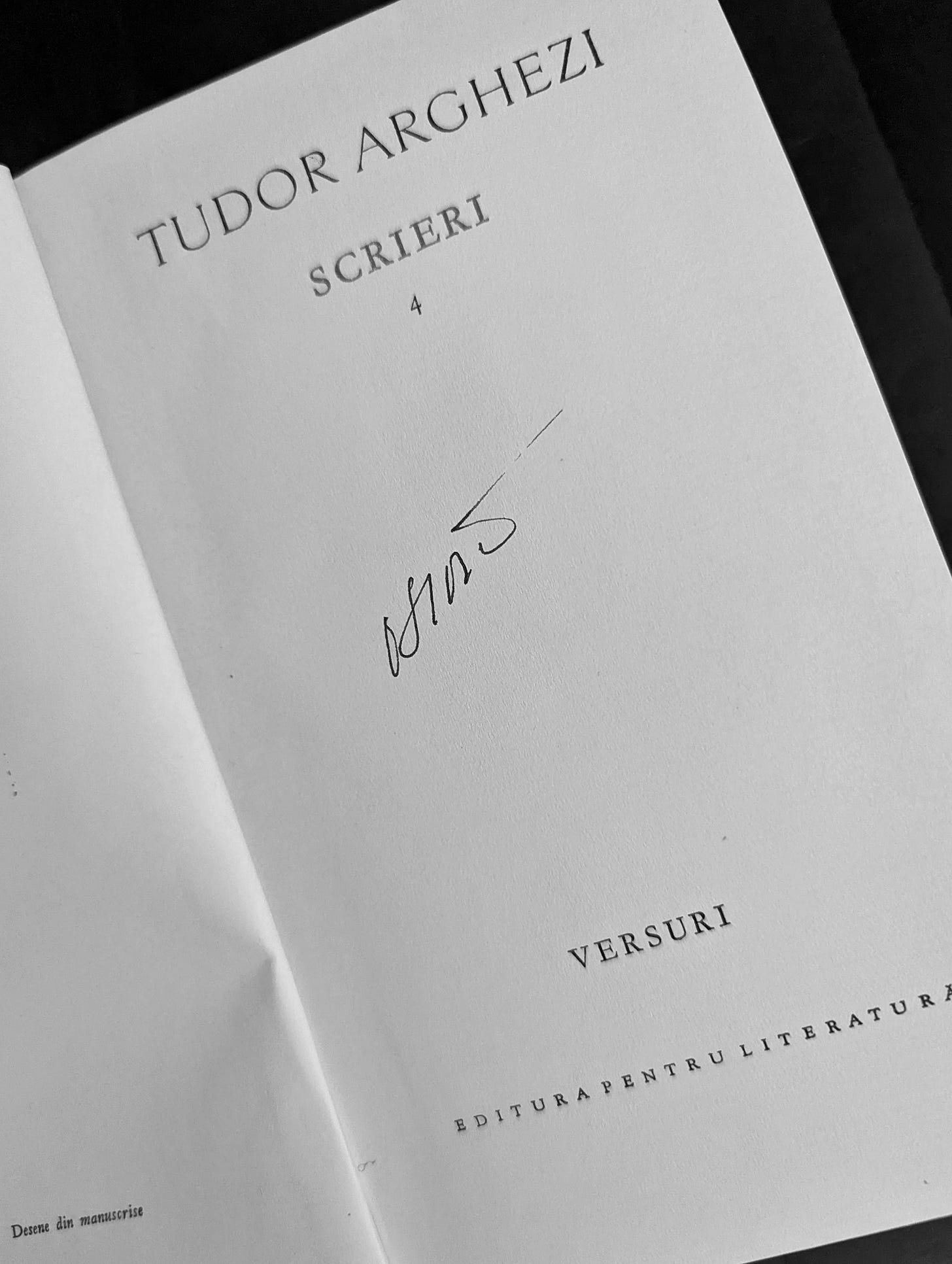

On my last night, alone with my grandmother, wife, and daughter already on their way home, I looked through albums and artifacts. Old pictures, furniture, and toys older than me. In one corner of the house a bookcase, one of many in the old house. Thumbing through the books I noticed that each one had a signature I didn’t recognize. It wasn’t my grandmother, who is my father's mother, and after thinking about it a bit she told me that most of the books on that shelf came from my other grandparent's house after my grandmother moved to Los Angeles. I took a picture of the signature and sent it to my grandmother in California. Right away she called me and told me that it belonged to her husband, my grandpa Dimi.

In Cormac Mccarthy's recent novel, The Passenger, my favorite character, Sheddan says to the protagonist, “But I will tell you Squire that having read even a few dozen books in common is a force more binding than blood.” To me, this is an undeniable truth. My grandfather Dimi was not my biological grandfather, but he raised me until his death when I was five years old. His presence, his memory, faded at times, has loomed large over my entire life.

Now after so many years I had books he read, books he signed, and took notes in, books he valued enough to keep over the years. I took as many as I could fit in my bag and I will keep and treasure them as a link to a past and home that is distant and fading.

I feel homesick for a place that does not exist...

May you, God willing, carry Grandfather Dimi with you until you are gone, and may you pass him along to your children before that time comes so that he can live on in them.