Life is shit, thought Pelletier in astonishment, all of it.

I’ve been averse to Latin American literature for a while now, thinking it was mostly magical realism where Abuelita makes magical empanadas and the mango tree Tito planted represents the soul of the village. So, out of this ignorance, I avoided everything from South of the Border and below the Equator. Until this year that is, when I discovered Roberto Bolano, whose work is now some of my favorite writing of all time.

I didn’t randomly come across Bolano on my own. I heard his name a decade ago when he became popular in the States, but I ignored his writing due to the above prejudice, until this summer when I was making my way through every episode of The Art of Darkness and listened to their great piece on Bolano. I was intrigued by what I heard, so I picked up Savage Detectives and read through it in a few days. I loved The Savage Detectives, it was up there with the best novels I’ve ever read, a masterpiece.

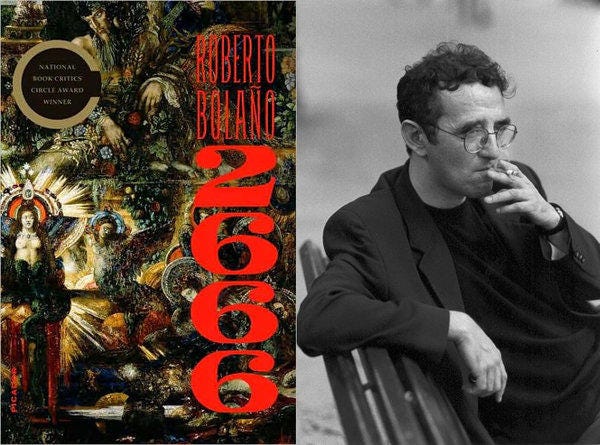

The Savage Detectives is a great novel and one I recommend you read first if you give Bolano a try, but his true masterpiece, his magnum opus is the massive 2666.

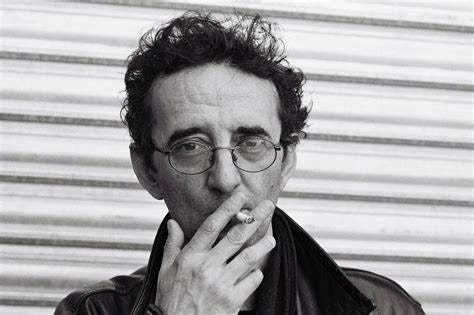

Roberto Bolano is interesting. He was born in Chile, but his family moved to Mexico around the time of the Pinochet coup, where he fell in with a bunch of Mexico City degenerate poets, artists, and an assortment of lefty types that make up the alternative scene in Mexico. He spent most of his life as a broke poet, moving between Mexico, Chile, and several European countries before finally settling down in Spain. He didn’t begin his writing career until he turned 40, at that time already with the knowledge that his health was poor due to a damaged liver. This led to a decade of frantic writing, giving us his two masterpieces, along with several shorter works before his death at 50.

2666 was Bolano's final masterpiece. A novel he frantically wrote during the last years of his life, waiting on a liver transplant. A novel he finished, but never got to revise or see its publication because he died before he got the chance. 2666 is the 1st manuscript of the novel, with minor edits based on Bolanos's notes, published posthumously in 2004, a year after his death.

The novel is a maximalist masterpiece, a fragmentary novel in five parts, unconnected except by the horrid uncountable murders of women in the Mexican city of Santa Teresa (a fictional city based on Ciudad Juarez) and the strange life of a literary enigma, a reclusive Prussian writer named Beno Von Archimboldi. The main thread of the novel is never approached in a straight line. Instead, Bolano weaves individual narratives, disconnected lives, that swirl around the connecting element, and in this case that element is the black hole of countless female corpses discovered in Santa Teresa.

Each of the five sections takes us on a journey filled with violence, sex, and murder, in an indifferent cold, and cryptic world. A journey of symbols and literary allusions from the academic halls of Parisian universities, the slums of Mexico City, the projects of Detroit, and the horrors of the Eastern Front in WWII. We follow academics, solitary writers turned soldiers, Jewish publishers, African American sports journalists, Mexican police detectives, and finally the women. Hundreds of them. Their butchered corpses were discovered in the slums of Santa Teresa, violated, and disfigured, in different stages of decomposition, many to remain unidentified.

The first part of the novel is The Part About the Critics. A surreal, almost Lynchian absurd narrative centering around four European Literature professors obsessed with the work of the elusive cult-like German author Benno von Archimboldi. The four critics, each from a different country, France, Spain, England, and Italy, dedicate their professional and personal lives to raising the esteem of the mysterious writer. What we get is a weird narrative as we follow these four characters from literary conference to literary conference across Europe, love affairs, including a bizarre love triangle between each other, and finally to the Mexican city of Santa Teresa, where they think that the now aging Archimboldi is hiding. It’s during this last part that we start to get the hint of the murders, the menacing background of impersonal authorities, and news reports of bodies found. In the entirety of this section, we get a feeling that beneath the banal and trivial lives, there is something wrong, that there is something out there, maybe in Mexico, maybe in the whole world. It’s unsettling, a feeling that something is about to happen.

Next, we have The Part About Amalfitano, a Chilean professor of literature who recently moved to Santa Teresa from Spain with his teenage daughter. This part, unlike the first, is mostly internal, about madness and obsession. Amalfitano is breaking down, hearing voices, and reminiscing about his wife who went insane and abandoned him and his daughter. The murders of women in Santa Teresa are closer now, much more threatening, because his daughter, the same age as most of the bodies, is going out at night with friends, clubbing, and getting involved with men. Amalfitano slowly breaks down, obsessing about a geometry book he finds. This section ramps up the uncomfortable dread that began in the first.

The Part About Fate returns us to the external with a narrative that is part American Detective Pulp and part David Lynch. Our point of view jumps to Oscar Fate, an African-American journalist who just found out his elderly mother passed away. After going home to her apartment and grieving he takes a trip to Detroit to interview an elder Black Panther like figure and witnesses a church sermon that alludes to the sermon that Ishmael sits through at the beginning of Moby Dick. From Detroit, Fate is offered a sports writing job that has him traveling to Santa Teresa to cover a boxing match. In Mexico he gets entangled with a series of Mexican journalists, and policemen, and spends his time drinking in bars, finally coming across the young Rosa Amalfitano. In this section, the murders are almost out in the open. There is an air of lingering violence and murder. Dread and confusion follow every step Fate takes. For example, this description.

The staircase ended in a green-carpeted hallway. At the end of the hallway, there was an open door. Music was playing. The light that came from the room was green, too. Standing in the middle of the hallway was a skinny kid, who looked at him and then moved toward him. Fate thought he was going to be attacked and he prepared himself mentally to take the first punch. But the kid let him pass and then went down the stairs. His face was very serious, Fate remembered. Then he kept walking until he came to a room where he saw Chucho Flores talking on a cell phone. Next to him, sitting at a desk, was a man in his forties, dressed in a checkered suit and a bolo tie, who stared at Fate and gestured inquiringly. Chucho Flores caught the gesture and glanced toward the door.

"Come on in, Fate," he said.

The lamp hanging from the ceiling was green. Next to a window, sitting in an armchair, was Rosa Amalfitano. She had her legs crossed and she was smoking. When Fate came through the door she lifted her eyes and looked at him.

"We're doing some business here," said Chucho Flores.

Fate leaned against the wall, feeling short of breath. It's the green color, he thought.

"I see," he said.

Rosa Amalfitano seemed to be high.

The above could be right out of one of David Lynch's works, strange hallways, music, drugs, green-lit lamps. A scene that would be at home in Twin Peaks or Mulholland Drive.

Finally, we get to the heart of the novel, The Part About the Crimes. This section is long and emotionally difficult. It’s written in short bursts, following Santa Teresa detectives, journalists, a psychic, the head psychiatrist of a mental institution, an American sheriff, and a television host. All of these characters are given to us in quick bursts, disconnected from each other except for the oppressive weight of the murders. The murders are what this section is about, it catalogs over one hundred murders, in plain administrative language, of women discovered in Santa Teresa between 1993 and 1997. This section is a work of art, taken alone, outside the greater work, it stands on its own as a commentary on the madness and horror of life and our inability to come to terms with it. It’s more often than not difficult to read, and I have to admit that while reading this part I started to feel sick, almost numb from the descriptions of death.

It begins right away.

The girl’s body turned up in a vacant lot in Colonia Las Flores. She was dressed in a white long-sleeved t-shirt and a yellow knee-length skirt, a size too big. The name of the first victim was Esperanza Gomez Saldana and she was thirteen.

Five days later, before the end of January, Luisa Celina Vazquez was strangled. She was sixteen years old, sturdily built, fair-skinned, and five months pregnant.

Midway through February, in an alley in the center of the city, some garbagemen found another dead woman. She was about thirty and dressed in a black skirt and a low-cut white blouse. She had been stabbed to death, although contusions from multiple blows were visible about her face and abdomen.

The next month, in May, a dead woman was found in a dump between Colonia Las Flores and the General Sepulveda industrial park. The dead woman had dark skin and straight black hair past her shoulders. She was wearing a black sweatshirt and shorts. The dead woman spent that night in a refrigerated compartment in the Santa Teresa hospital and the next day one of the medical examiner’s assistants performed the autopsy. She had been strangled. She had been raped. Vaginally and anally noted the medical examiner’s assistant. And she was five months pregnant.

The first dead woman of May was never identified, so it was assumed she was a migrant from some central or southern state who had stopped in Santa Teresa on her way to the United States. No one was traveling with her, no one had reported her missing. She was thirty-five years old and she was pregnant.

On and on, and on, and bloody, on the horror continues, only broken up by police narrative and failed investigation.

Pages and chapters of clinical reports of murders, unsolved, and the police and journalist efforts, often incompetent, trying to find the killers. Detailed police descriptions of stabbed, choked, raped, young women, often as young as 13, leave you nauseated. This section is rough because you get the sense that no fancy detective work will solve these crimes, there is no motive, no purpose, just life in a struggling city on the edge of Mexico.

This section is a masterpiece, a black hole of despair, that will stain you, and leave you feeling almost complicit in the murders. With this section, Bolano achieves literary supremacy, stylistically and thematically. Unforgettable.

Finally, we arrive at the end, The Part About Archimboldi, where we learn about the life of the elusive author Benno Von Archimboldi. The first three parts of 2666 were a tension funnel, where strangeness and violence lurked in the background, and with each section slowly slithered forward. The fourth section was the explosion, the full, realist view of a spiritual void that destroyed the lives of everyone it touched. But, with this final part Bolano takes us back to Europe, and returns to the world of literature, but unlike the first section this world is also one of violence and horror. We follow the young seaweed-obsessed son of a WWI amputee living in 1930s Nazi Germany, working as a servant at the forest retreat of a wealthy family. From there we follow him as a soldier on the Eastern Front, through Ukraine, Romania, a strange episode at Dracula’s Castle involving the Iron Guard, post-war love and death, and finally to an anonymous literary career and love that brings him around to Santa Teresa, Mexico.

Just like the real murders that took place in Cuidad Juarez, the murders in 2666 do not get solved. There isn’t a happy ending, there isn’t closure. Just ice cream.

2666 is a difficult, complex masterpiece, a must-read for any serious appreciator of literature. But I warn you, it’s rough, it digs its way inside of you and makes itself hard to forget. It’s a maximalist novel that rivals the best of Pynchon, but unlike Pynchon, it lacks the self-deprecating American irony and silliness. There aren’t any talking dogs or rat churches in 2666, just the disfigured and raped bodies of unknown women.

Along with Mircea Cartarescu’s Solenoid, I hold 2666 to be one of the best novels, if not the best, to come out of the 21st century. Nothing else comes close.

Thank you for this review. I feel better-equipped for when I eventually get to this book.

Really wonderful write-up - has firmly convinced me to read this book!